Margaret's memories of service on the land

Margaret Elliott was a city girl.

In her youth, when her maiden name was Field, the closest she had come to farm life was visiting her grandparents’ farm at Colebrook during summer holidays.

So, when at age 16, she volunteered to help the war effort as a member of the Women’s Land Army, she had no idea how long the days nor how physical the work would be as part of a female workforce trying to address the farm workers’ shortage caused by World War II.

Along with Ruby Anderson and twins Muriel and Mavis Jacobs, she was recruited by Manpower and sent from Hobart to Cressy, the site of Australia’s first AWLA training school set up at the Cressy Agricultural Research Station.

Here they received hands-on experience in dairy, sheep and piggery work, working horse teams, tractor driving and equipment maintenance.

From there she was moved to the Scottsdale Commission, established in 1944, where the girls were housed in rooms under the old showground grandstand while huts were built at what became known as Wonder Valley on the banks of the Great Forester River, north-east of Scottsdale.

They were given a hat, overalls and boots to wear and scratchy woollen undergarments, quickly discarded with the excuse that they had “shrunk in the wash”.

Taking over from experienced farm hands, they ploughed and sowed fields using horses and some of the early tractors, took care of the crop harvest and simply did whatever they were told to do on their assigned farms.

At Scottsdale most of the produce went to the local dehydration factory for military supplies.

By the time the women had fulfilled their duties ensuring the nation and the troops were fed, and the unit was disbanded at a special ceremony in Scottsdale on September 21, 1945, District War Agricultural Committee chairman Mr R.J. William said the land girls had “proved to be of sterling worth and efficient”.

This was to be one of few acknowledgements of the crucial role they fulfilled, as they were quickly forgotten and deliberately ignored, with all records of the AWLA ordered to be destroyed.

As a voluntary group, and not an enlisted service, they were not accorded the same rights and benefits of other women’s services until 1985. They were even denied the opportunity to march on Anzac Day.

Finally, in 1995, AWLA members were officially recognised and became eligible for the Civilian Service Medal, and Margaret applied for hers and unceremoniously received it in the post.

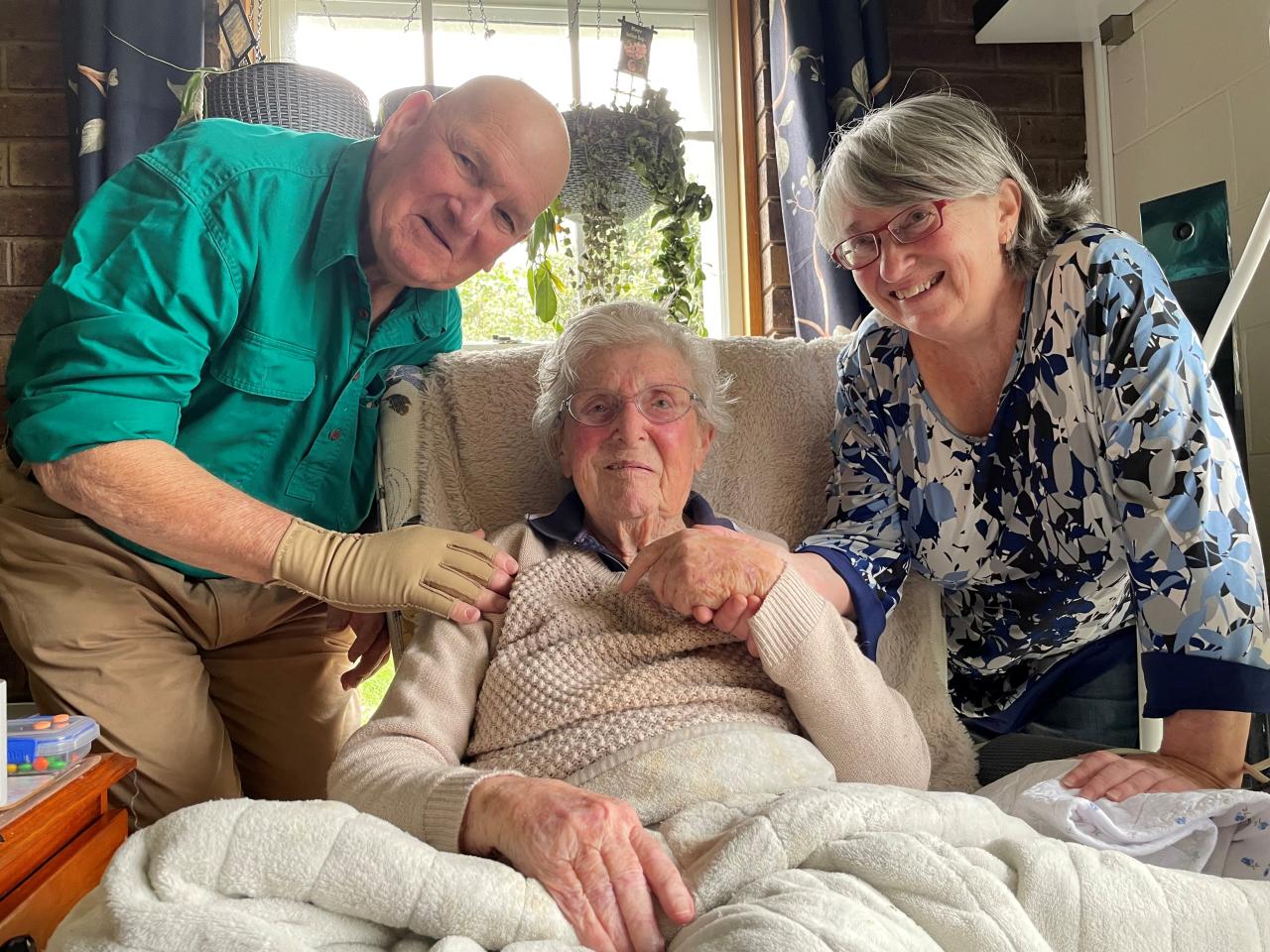

Now living with her daughter Deborah at Kempton, Margaret holds onto many stories about the AWLA and the farming communities that shaped her life.

“It was hard work but I enjoyed it. We got to do things that most girls weren’t allowed to do back then and we had freedom in a way,” she said.

“It was especially good for someone like me who didn’t have a great start to life.”

Margaret was born in West Hobart and her mother died when she was four, her older brother died when he was only eight, and those traumas attributed to her father becoming an alcoholic, so she ended up being raised by her aunty, who had six children of her own.

Cousins became more like siblings and one of the boys, Laurence Shepheard, signed up when the war broke out and was eventually taken prisoner by the enemy in Timor.

Hearing about his plight through her auntie, Margaret understood the ramifications of war from an early age and after finishing school in grade 6 and getting work as a clerk at Webster Romtech bus company, she signed up through Manpower recruiting to do her bit for the war effort.

She didn’t want to end up working in a factory like many other girls and unlike her best friend Bonnie, she was too young to join the Airforce, so she joined the Women’s Land Army.

After being trained up and having turned 18, she said her first assignment was working at Scottsdale for the McClennan brothers, Athol and Mervyn, who grew vegetables for the 250,000 American troops sent to Australia to help fight the Japanese in the Pacific War.

“We were up at around 5am and I got to drive a tractor and to work a collie dog,” she said.

“Sometimes we’d check apples for blemishes before they went through to the girls in the factory.”

Margaret remembers being sent to the train station with sacks of potatoes destined for the American troops, when an American inspector checked a bag and found a blemish on a spud.

“He made us unpack all of the potatoes and check every one for marks, saying they were not good enough for his men.”

Socialising was usually based around the local dances on a Saturday night.

Every day was an adventure, with hard work broken up by the typical mischiefs of youth and plenty of drama.

“There were snakes everywhere on that farm, and one old chap who used to get his boots from under his bunk in the morning reached under and then felt something on his hand, he thought it was a snake bite so he got an axe and chopped his fingers off!” Margaret recalled.

“I found one in my bed one night and luckily I didn’t get bitten, there was no way I was going to do that!”

While some of the girls, which over time swelled to about 20 in number, had pushbikes, Margaret had to borrow a horse from the farm to go into town.

“I was galloping down the main street of Scottsdale one day and he shied at something on the railway line and I was thrown off and I broke my wrist,” she recalled.

"I had to go home for a while because I couldn’t work.”

Other than some annual leave or through injury, the women didn’t return home during their three or four years in the Land Army and they missed their families and homelife despite embracing their independence.

Margaret earned herself another trip home after a boiling pot of water tipped off the stove and down the back of her legs.

“Merv picked me up and took me to the hospital and kept giving me drinks – by the time I got to the hospital I was rather drunk!” she laughed.

Margaret also spent some time on a mixed farm at Buckland with a Mrs Mace and her daughter, while farmer Stan Mace was away and for a Mr Salier on a flower farm at Scottsdale.

She has fond memories of a Mr Dunning, another assignment on a farm that grew Loganberries at Oyster Cove,

“He spoilt me,” Margaret said.

“He wouldn’t let me work in the rain, if it was too cold he wouldn’t let me go out to work at all.

“He didn’t have a daughter so I think he treated me like a daughter."

A small stint was at Palmerston, Cressy, where the lady of the house was extremely particular and only allowed her to enter one room to have her meals, and she remembers the O’Connors at Connorville next door.

By the time the war ended Margaret was at Cygnet in a packing factory, something she didn’t enjoy as much as the farming and the one thing she had hoped to avoid because “good girls didn’t work in factories”.

Around this time she met her husband Adrian at a dance at Campania and they were married on November 16, 1946 at Holy Trinity in Hobart – he had only had to serve 12 months with the Air Force due to being required on the family farm at Brown Mountain.

They had nine children, six girls and three boys, with three now deceased and Geoffrey, Peter, Denise, Christine, Deborah and Amanda still alive and still in awe of their mum and her adventurous youth.

Add new comment